This week, I would like to take an extreme example of adventure and focus on my next word in the A-Z of personal development – ‘belay‘.

You might wonder why I have chosen such an obscure word. Please bear with me!

What does the word mean in my Collins dictionary? ”to fix a rope around an object to secure it.” There is more to add to this definition actually – I know this as a former professional rock climbing instructor. So what does the word mean in more detail?

A belay has two functions. One is to securely anchor a climber to a mountain side so there is no movement, and the other is to provide a point from where all the remaining rope attached to another climber (let’s assume there are two roped together here) can move upwards. So it needs to be both a static place of safety and a dynamic place of progression.

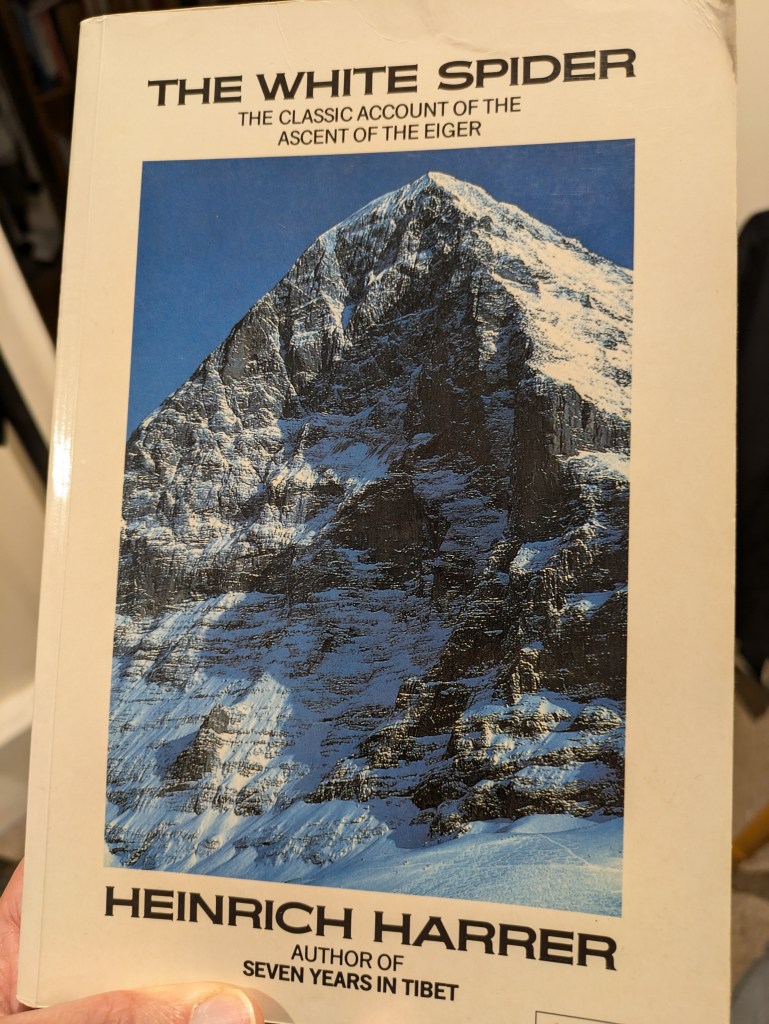

As I was reading Heinrich Harrer’s classic account of the first ascent of the North Face of the Eiger, called ‘The White Spider’, it struck me just how critical these belay systems were. They are to the climbing world what a sail is to a skipper. If you arrange two sails on a boat in a certain way you can ‘heave to’, which means stop without using an anchor. Or you can arrange the sails to harness the wind and make progress.

Before 1938, nobody had climbed the North Face of the Eiger, though plenty had already died trying. It was seen as the most challenging place to climb in Europe, and steadily attracted the top climbers and mountaineers of the day to attempt it throughout the 1920s and 30s. Even with World War Two imminently starting, there was a frenzy of activity on the North Face in the late 30s. Heinrich Harrer was a member of the team who made the first successful ascent, and spent much time afterwards researching previous teams who had made attempts and reflecting on what climbing was all about and how it helped people to progress as different people afterwards.

He says that ”to climb this mountain is to discover something entirely new, if only about yourself.”

Reading the book, there are two things that strike me in particular. The first is that each and every ascent is different – kind of like climbing a different mountain each time. And secondly that no two climbers that succeed are the same in terms of their personality. This second point might seem obvious but when you think about it, it’s a bit puzzling. This mountain is incredibly challenging, and for most things that require such a high level of skill and courage you would think that successful climbers would have to be of a similar mindset, skillset and ability. Or put another way, that the challenge would filter out those who were not of the right standard to finish it. Like an Olympic 100 meter sprint where every athlete at the starting line has a very similar physique, training schedule, diet, routine etc etc.

Harrer again: ”all the climbers who attempted the Face were sharply defined personalities. No two of them were alike.”

While researching for this post, I came across the story of Sir Ranulph Fiennes, a major celebrity in the world of exploration and adventure. He has climbed the North Face of the Eiger, guided by Kenton Cool, for a charity fund raising event. You might think this makes it sound less of a challenge than 1938 teams had it, but very much the opposite. The Face is still regarded as an extremely serious undertaking for climbers in modern times, so much so that it remains one of the final test pieces of climbing before a person can submit their application to become a qualified Mountain Guide. The fact that Sir Fiennes climbed it while trying to overcome his fear of heights is incredible (he had only had one year of training before climbing it – the average is ten years) and he was reported as being a bit ‘clumsy’ as a climber. Just goes to show that having a ‘sharply defined personality’ and a bucket load of self confidence is the key to overcoming some of the challenges that adventure can throw at you.

So this climb is not just a journey of discovery measured in how good you are at making belays in snow, rock and ice. It’s also a measure of professional accomplishment, the test piece to demonstrate mastery of personal confidence, and a rite of passage for any aspirant seeking to complete the Six Great North Faces of the Alps.

Coming back to the keyword of ‘belay’ for a second. A big climb such as the North Face of the Eiger will require hundreds of things called ‘pitches’. These are measured in rope lengths. E.g. one pitch might be 50 meters. So you climb 50 meters, make a belay, then bring your partner(s) up, make everyone safe, then make some progress.

Imagine your goal like a series of many pitches. When you make one step forward, it’s a save point, where you can make progress from, rest for a while, or turn back. Without them, you will very quickly find yourself burned out, demotivated and maybe even in danger!

I’ll finish with one more quote, which I think is particularly excellent.

Harrer again: ”…explore a mountain from every angle before tackling its most difficult side.”

If you’re choosing a goal that is really difficult, it is wise to have completed the easier aspects of that goal first.

Next week, I study the word ‘believe‘ and read the incredible story of how 13 young lives were rescued from a cave in Thailand…

”

Leave a comment